Research

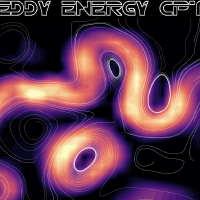

Ocean Transport and Eddy Energy CPT

I am part of the Ocean Transport and Eddy Energy Climate Process Team. This CPT is a large collaborative project funded by NOAA and NSF. So far, my contribution to this project has been the development and implementation of an algorithm that applies lateral surface eddy-diffusion in MOM6.

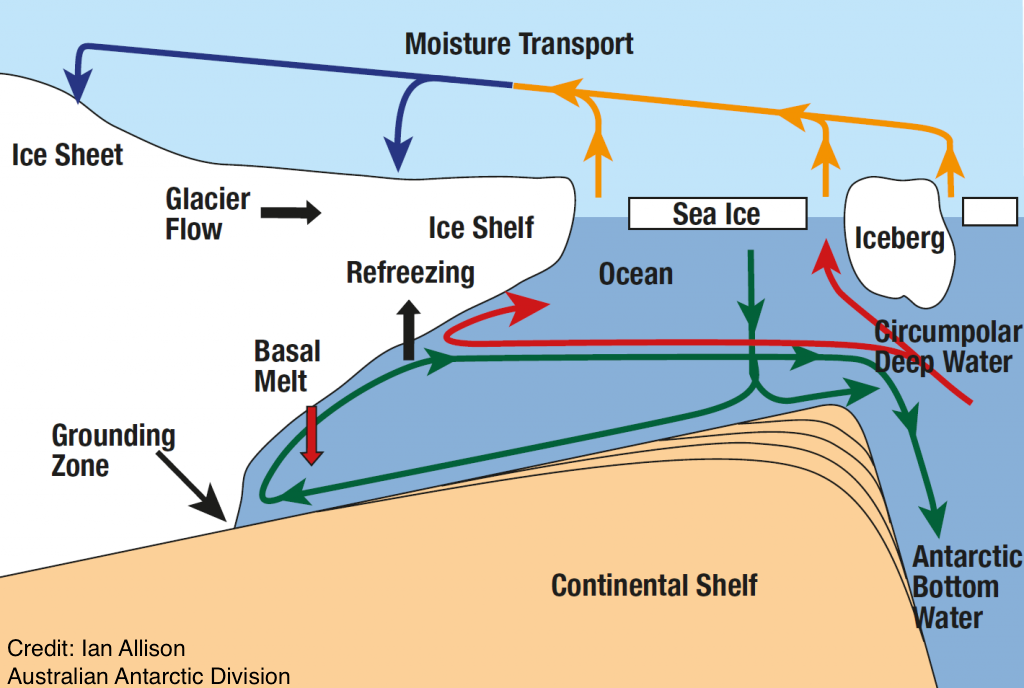

Ice/Ocean interactions

One of the most difficult problems associated with climate change is the correct estimate of how much global sea level will rise over the coming century. Part of the answer to that depends on physical processes that take place in regions where the atmosphere, ocean and cryosphere interact. These processes are key players in controlling the melting of ice shelves, which are floating sheets of ice connected to a landmass. Since ice shelves buttress the glaciers behind them, once they break or collapse a large amount of ice can then be added to the ocean and contribute to sea level rise. My goal is to understand the role of different physical processes in controlling the circulation underneath ice shelves as well as the heat exchange between ice shelf cavities and the adjacent ocean. I am involved in the 2nd Ice Shelf-Ocean Model Intercomparison Project (ISOMIP+) and Marine Ice Sheet-Ocean Model Intercomparison Project (MISOMIP) projects, where I am responsible for conducting the experiments using GFDL's ocean model (MOM6).

Oceanic overflows

Ocean overflows (or gravity currents) occur when dense water formed along continental shelves flows towards the deep ocean over a sloped sea floor. Some of these currents play a crucial role in the large-scale ocean circulation and, therefore, are an important component in Earth's climate system. Despite recent increase in computer power, oceanic overflows are poorly represented in ocean models and this is a key challenge for improving climate predictions. One of my goals is to advance the understanding of physical processes occurring in oceanic outflows so that future observational and modeling efforts can be improved. Check the following paper to learn how overflows can generate topographic Rossby waves:

Marques, G. M., L. Padman, S. R. Springer, S. L. Howard, and T. Özgökmen, 2014: Topographic vorticity waves forced by Antarctic dense shelf water outflows. Geophys. Res. Lett., 41, 1247–1254, doi:10.1002/2013GL059153. | PDF | online

Modeling Buoyancy Driven Flows in OGCMs

Ocean General Circulation Models (OGCMs) are the primary tools for predicting ocean currents and changes in the ocean’s stratification. Most OGCMs integrate the hydrostatic primitive equations using a variety of horizontal and vertical coordinates, mixing parameterizations and advection schemes. For problems that require relatively small spatial resolution (i.e., submesoscales and below) these models start losing validity due to the hydrostatic approximation. I've conducted a study that compares the mixing and stirring in buoyancy-driven fronts derived from two modeling approaches: 1) using an OGCM (ROMS) versus 2) using a non-hydrostatic model (Nek5000). Common OGCM's modeling choices were tested, namely spatial resolution, tracer advection schemes, Reynolds number and turbulence closures. Mixing is more sensitive to the choice of grid resolution than any other parameters tested. More details can be found in the following paper:

Marques, G. M., and T. Özgökmen, 2014: On modeling turbulent exchange in buoyancy-driven fronts. Ocean Modelling, 83, 43-62, doi:10.1016/j.ocemod.2014.08.006. | PDF | online

Tidal eddy-motions in the Western Gulf of Maine

The western Gulf of Maine has a high concentration of sea scallops and others economically important species and, therefore, is a valuable region for the local fishing industry. Motivated by observational evidence of the formation and evolution of transient tidal eddy motions, I was part of a study that used observations and numerical simulations to elucidate the kinematics and dynamics of the tidal circulation in this region. We found that the formation and evolution of the transient eddy motions are controlled by the spatially varying influence of bottom friction on the dynamics. The full study can be found in the following papers:

Brown, W. S., and G. M. Marques, 2013: Tidal eddy motions in the western Gulf of Maine, Part 1: Primary Structure. Contin. Shelf Res., 63, S90-S113, doi:10.1016/j.csr.2012.02.008.| PDF | online

Marques, G. M., and W. S. Brown, 2013: Tidal eddy motions in the western Gulf of Maine, Part 2: Secondary Flow. Contin. Shelf Res., 63, S114–S125, doi:10.1016/j.csr.2012.02.008. | PDF | online